What is manifold pressure?

Here is a simple enough question that made it to my inbox today:

What exactly is meant by Manifold Pressure?

The manifold pressure gauge is an engine instrument typically used in piston aircraft engines to measure the pressure inside the induction system of an engine. In other words, it literally reads the pressure inside the induction system.

Correction: A good pilot is always learning right? Well, since writing this post I have learned that the manifold pressure gauge is really NOT about pressure but about suction! Think about it. Your whole engine (especially the cylinders) is a big vacuum pump. Every time the piston drops into the “intake” stroke it is literally pulling or sucking air into the cylinder. Your manifold pressure gauge is actually reading suction not ram air pressure. That’s why at idle power your manifold pressure gauge might read 10 or 12 inches when the outside ambient pressure is 30 inches. Your engine is literally starving for air! It is creating a vacuum or negative pressure inside the intake manifold.

The induction system of couse being the air / fuel mixture that is between the throttle and the cylinders.

This measurement, which is read in inches of mercury or “in hg”, is one of the best methods to determine just how much power is being developed by the engine. The more air and fuel we can pump or pull into the cylinders, the more power the engine can develop (which makes us fly faster). When you can measure how much air pressure is in the induction system, just before the air / fuel mixture enters into the cylinders, you will have a good idea of how much power you are developing.

In normally aspirated engines (non turbo-charged), the manifold pressure gauge has a range of anwhere between 10 – 40 in. hg (or inches of mercury). In a turbocharged engine, the manifold pressure is allowed to go as high as the engine manufacturer allows. When the engine is shut down, the manifold pressure gauge should read very close to the current atmospheric pressure setting.

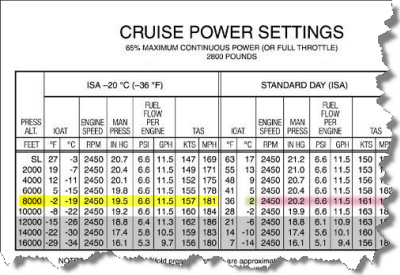

In order to equate manifold pressure to aircraft performance we need to look in section 5, or the performance section of our Airplane Flight Manual:

Take a look at this sample above. You can see that at 8,000 feet pressure altitude, -2 C, and 2,450 RPM we would be developing about 19.5 inches of mercury in the induction system. You can also see how that would then be related to fuel flow and our true air speed.

Take a look at this sample above. You can see that at 8,000 feet pressure altitude, -2 C, and 2,450 RPM we would be developing about 19.5 inches of mercury in the induction system. You can also see how that would then be related to fuel flow and our true air speed.

Douglas Adams on Mar 11, 2009

Paul,

This is a very good explanation. I was actually looking to see they made such a device for automobiles when I ran across your article. Very easy to read and understand. Thank you for your time and keep up the good work!

Douglas

Thyrso Guilarducci on May 24, 2009

It’s really good to read and comprehense explanatiuons from website yours. Thank you.

ghafoor khan on Sep 04, 2009

it is realy good and comprehensive explation . i saw first time in my 29 years of working as aircraft instrument technican being always remain in doubts in its operation and behavour of work.

Sonny Cropley on Oct 02, 2009

Paul

I have a SEL certificate with just over 200 hrs. I plan to move up to complex with constant speed props. I understand how to adjust the throttle and rpm but I don’t know why and how this changes the manifold pressure. My problem is that I’m a mechanic and I feel the need to understand the mechanics of this mechanism

John on Mar 17, 2010

How doe the reading on a vacuum gage correlate to the manifold pressure gage?

I assume zero on the vacuum gage is atmospheric then if I see a drop from 24 in hg on the vacuum gage to…let’s say 5 in hg then what would that be equivelent to on a manifold pressure gage?

Sumone on Mar 26, 2010

In a normally-aspirated engine (not turbocharged or supercharged), the manifold “pressure” gauge is _always_ measuring a vacuum, i.e. a pressure _less than_ atmospheric. This is because an internal combustion engine acts as a vacuum pump during the intake cycle when the piston is going down and the intake valve is open. The piston is trying to _suck_ fuel and air into the combustion chamber. It is restricted from doing so by the throttle plate (more on that later), creating vacuum behind the throttle plate and as measured by the MP gauge. At all other times the intake valve is closed and what is going on with the piston and cylinder does not register on the MP gauge. Since you have 4 or 6 cylinders going, you always have some cylinder in an intake phase.

The MP gauge is measuring in _absolute_ pressure. That is why it says ABS on the face. Absolute pressure means relative to absolute zero pressure, total vacuum. It is measuring pressure in inches of mercury (in. Hg), the same type of unit you enter into your altimeter. With the engine off, the MP gauge should read the same as the “altimeter” pressure, minus any adjustment for altitude. So John, an MP gauge reads 30 or so at atmospheric while a vacuum gauge would read zero.

At low power settings, e.g. idle, MP is low, say 10-12 in. Hg which indicates that the throttle plate is closed and we are generating vacuum behind the throttle plate. As we increase load, we see the MP increase because the throttle plate is open and “throttling” less, i.e. choking the flow less, so there is less vacuum (more absolute pressure).

Hope this helps.

Peter on Jul 11, 2010

I don’t understand the relationship between the temperature, MP and TAS showed in the cruise power setting table.

Can you help me?how do i have less MP and TAS with ISA – 20?

Thanks

mateo on Jul 21, 2010

how possible is it to have low MP and high engine temperature?

Why does manifold pressure increase during a prop check? | Ask a Flight Instructor on Jul 26, 2010

[…] This is a follow-up question to an earlier post entitled “What is Manifold Pressure ?” […]

Mike Geronime on Aug 27, 2010

Great answer, and great site. I’m now watching a WWII training film for pilots about to fly the TBF Avenger. Manifold pressure is brought up over and over again. Now I understand what they’re talking about! Thanks.

Stew Lustgarten on Jun 10, 2011

One must not confuse pressure with velocity. The lowest of all air or vapor pressure is a complete vacuum. As pressure increases, velocity decreases and as velocity increases, pressure decreases. It’s also the principle of flight for the wing is 1/2 of a venturi forming a low pressure area on the top surface by increasing the velocity of air flowing over it and with a decrease in pressure beneath, causing lift.

It’s essential to have a manifold pressure guage for each engine in an aircraft for the guage will indicate the first signs of a failing engine by loss of manifold pressure.

Scott Whitcher on Jul 16, 2011

Just a note. Look at the bottom of the gauge shown and you will see “Manifold Pressure- IN HG ABS”. This means Inches of mercury ABSOLUTE, which means that the gauge reads “ABSOLUTE pressure”, as opposed to “GAUGE pressure”. Zero “absolute pressure” is a complete vacuum. Zero “guage pressure” is atmospheric pressure, which is 29.92 inches at sea level on a “standard” day. Anything above 29.92 inches of mercury (IN HG ABS) would be positive if read in “gauge pressure”. Anything less would be considered a partial vacuum.

Since normally aspirated engines cannot have manifold pressures above atmospheric

(less once the engine is started) they are often (particularly in automobile mechanics) read as “vacuum” in “inches of mercury”. Aircraft often are turbcharged (an many old warbirds are supercharged with engine driven centrifical blowers), so the manifold pressure can be above atmospheric. Manifold pressure and is a means of determining

torque (and the stress on the engine). Torque and RPM determine horsepower, so a chart can be made with manifold pressure on one edge, RPM on another and horsepower at the intersection.

All this to say that aircraft manifold gauge pressure is not vacuum but pressure measured from above an absolute vacuum.

J on Aug 22, 2011

in the initial explanation. How is it possible that a normal aspirated engine (not turboed) can produce 10 – 40 hg on the mp gauge. Is that typo, does he mean 10-30 or 10- 29.92 to be more exact.

Mbayi on Feb 03, 2012

This is a good article for both students and people doing research.

MJ on Mar 04, 2012

I am looking at the chart above which highlights 2C or -19 F degrees and then reading the text below it, and it says -2C. Is this a typo or am I missing something?

H.A.S on Apr 19, 2012

Manifold Pressure gauge reads Atmosphric Pressure. So where ever you are at in the world, when the engine is setting not running, this gauge will read your current Atomosphric pressure where you are in the world.

No fire up your engine and close the throttle to idle. Now this gauge is reading how far open your throttle plate is and allowing Atomosphric pressure in. So at idle you are reading real low on this Mainfold pressure gauge.

Now as you open the throttle plate it opens up the intake to more Atomosphric Pressure and the gauge reading starts to go up.

Now open her up all the way. You will notice that the reading does not reach outside Atomsphric pressure. This is becuase the engine needs some of this pressure to run normal aspired. It will be close to out side pressure but not quit there.

So you can use this gauge to measure how much load you are putting on the engine, or how much you are making it work. The lower this Manifold Gauge is reading the less you are working this engine. The higher this gauge reads the harder you are working this engine.

pete worrall on May 27, 2012

Very informative. Now I know what “manifold Pressure” really is and what it means to a pilot.

Novanda on Jun 14, 2012

MAP sangat penting untuk pesawat bermesin piston engine.

reicarl on Jul 23, 2012

sir, what will happen if the reading of manifold pressure is over the limit and if it is greater than the tach generator reading??? can anybody know what will happen?

Andres on Sep 20, 2012

reicarl, I don’t know too much about engines, but this could be happening because the intake valves are not closing correctly, and the pressure inside the cylinders, resulting from the combustion is outflowing to the manifold, thus increasing the pressure. Somebody let me know if I’m wrong.

Nick on Oct 10, 2012

Thanks, Paul: I was always confused by the concept of manifold pressure because I always thought that the intake portion of an engine was under vaccuum (unless super- or tubo charged). Therefore, in all cases with an engine running, MP would always be less than atmospheric presssure, and the lower the difference, the higher the power setting.

So in a normally-aspirated engine, MP can never exceed Atmospheric pressure, correct? Therefore, at 10,000ft, where the atmospheric pressure is approx. 21 inches Hg, MP could never get above 21 inches.

Also, I believe you mean -19C in your reference to the Power Setting Chart (not -2C). To reicarl and andres, all intake valves must be closed on any piston upstroke (exhaust or compression stroke) or the engine won’t run.

Joe on Feb 09, 2013

Excellent explanation! thanks

Skeet Baldwin on May 10, 2013

This is great dialogue. So because the higher the altitude the greater the need for a super/turbo charger to compensate for the lower absolute air pressure so the pilot may produce more power from his engine to say dogfight or carry bomb tonnage. Right.

Jimmy Carter on Jun 17, 2013

This is great one instruction! I got print it keep for my file.

“Glorious Flying In Skies”

Long Live Spartan Executive/WACO

James

Henry on Sep 07, 2013

Actually, your original statement is correct:

“In other words, it literally reads the pressure inside the induction system.”

‘Suction’ is just a relative reduction in pressure. It is still pressure.

Much how ‘deceleration’ and ‘acceleration’ are the same thing scientifically, but negative acceleration is called ‘deceleration’ in layman’s terms.

Similarly, ‘suction’ is when the relative air pressure is ‘backwards’ from what you are expecting – but it is still a ‘pressure’

-Henry

Steve on May 11, 2014

Got it now.

What is so confusing is the word “pressure” and the fact that this is not measured in metric.

In BAR is would be clearer with +1 bar being “ground level” pressure, 0 = vaccuum.

So anything below abt 1000mbar would be vaccuum whereas turbocharged engines go way above +1.

NAC on May 21, 2014

Now I get it. Going to sit my air tech exam on Monday and this surely has helped me understand what manifold pressure is..

Bill McGraw on Jun 25, 2014

What is MAP in relation to MP gauge?

JohnD on Jun 25, 2014

Great info but think of your “Correction” again. Once you put a supercharger on an engine, suction is not the case.

Emerson on Sep 17, 2014

Hi So would a twin engine aircraft have two gauges? I looked in the P38 cockpit and it only had one. I bought two at a show and was told they might be from the same aircraft definitely a US ww2 one. Any ideas on where they might be from?

fernando perales on Nov 12, 2014

To the comment where intake and exhaust valves are closed well they are not.Before tdc on xhaust the intake will open 20 degrees btdc this creates what is known as volumetric pressure.You have to have this for complete cycles to obtain…

Bill Allen on Jan 26, 2015

OK, I get this fine. I just don’t understand why it’s labeled manifold “pressure” rather than “vacuum”.

Ian Fleming on Jun 01, 2015

Do not think in terms of suction, it’s all about pressure. An engine is NOT a vacuum pump it’s an air pump. As the piston goes down, air is NOT sucked in, it is blown in at atmospheric pressure. To control the amount of air blown in, we use a throttle plate to block the intake, restricting the amount of air and fuel, and therefore the amount of power made. Therefor carburettors do not suck, they blow! If we supercharge the cylinder we blow air at pressures above atmospheric and referred to as Boost.

Sometimes this used to increase the amount of power an engine makes, or as is often the case with turbochargers to turbo normalize, or keep manifold pressure at sea level values as the aircraft climbs therefore maintaining engine power output that would normally decrease as altitude increases.

Manifold pressure gauges measure barometric pressure in the intake manifold and the numbers just happen to jive with RPMs, hence the 24/24 terminology (2400 rpm, at 24 inches on the manifild pressure gauge, and so on. Old ’round’ engines were susceptible to damage in some conditions if they were operated over square, ie the manifold pressure was higher than RPMs. More modern opposed engines do not suffer from the same problems and can be safely operated over square as long as a cyl head temp gauge is used to monitor each head temp to detect detonation.

Will on Jun 09, 2015

Excellent info. I have finally got MP correct in my head. Ian did a great job in summing it up and making it crystal clear.

Ravinder Brar on Aug 09, 2015

“There is on such thing as suction, it is just differences in pressure.”

-Quote from my power plant teacher who has his own FBO and has been in the business for a while.

Just like you said the engine is creating a lower pressure in the manifold because the throttle (butterfly valve) controls the amount of air you allow the engine to intake. As the piston travels down it creates a lower pressure inside the cylinder which naturally creates a flow between the manifold and cylinder and as the piston reaches Bottom Dead Center the pressure in the cylinder and manifold equalizes to what ever the manifold maybe (15-30 inches or more if you have a supercharger).

I wrote this prior to finishing reading your post and any post of the responses, I scrolled up and Ian Fleming has the right idea.

Nic on Sep 10, 2015

Great explanation – thanks

So why does the MP increase during a prop check???

GARY THOMPSON on Feb 16, 2016

HI: WE HAVE A 0-300 D 145HP C172 WE HAVE A MANIFOLD PRESSURE GAUGE. IS 24INCHES EQUAL TO 75% POWER AT ALL ALTITUDES? WE ARE BREAKING IN A NEW ENGINE. THANKS, GARY

Scott R Cannon on May 11, 2016

So, what is the difference between COMPENSATED and UNCOMPENSATED manifold pressure gauges? Are you discussing an uncompensated gauge?

sabarinath on Aug 10, 2016

thank you for this article

both aircraft &automobiles

Mohamad Faiz Bin Azlan on Dec 05, 2016

What problems that can be indicates by manifold gauge ?

Adriana on Apr 04, 2017

Can anyone tell me if the MP has mercury in it?

Thank you

Muhil on Jul 17, 2017

Sir, you’ve mentioned there as -2°C but it’s not Celsius but it’s °F and Celsius is -19. Thank you for Your Valuable Information.

wayne peterson on Sep 17, 2017

So if If I understand correctly, the manifold pressure gauge reads the difference between outside air pressure on a standard day, and negative pressure in the intake manifold. So how does that work on supercharged aircraft? I’ll use as an example the WW2 P 47. At high power settings it would read over 50 inches. Obviously this reading isn’t negative intake manifold pressure, so is the gauge different or does the gauge read at a different point in the induction system?

Jeff on Sep 21, 2017

Your MAP gauge is literally reading outside air pressure as it enters the engine. When your engine is off (no vacuum being produced by the running engine behind closed throttle blades), its reading is equal to outside air pressure.

If it were reading vacuum, why is it so high with the engine off? Its literally displaying “pressure” in your engines intake manifold, which is reduced by vacuum. Thats why its called Manifold PRESSURE gauge, not a Manifold VACUUM gauge. (they both exist)

When you start the engine, vacuum forms, and this pressure displayed on the MAP is reduced due to the restriction in your intake.

When you go wide open throttle, the gauge is again reading nearly identical to outside air pressure (however you still have restrictions in your intake: eg air filter, intake tract etc), so there is some vacuum still being formed with the engine running at WOT)

Next time you are in your airplane, do this: Check the local altimeter setting. Lets say its 30.00″

Now take your field elevation. Lets say its 4,000′

Subtract 4″ (1″ per thousand feet) from 30.00. This gives you 26″. Guess what your MAP gauge is going to read before you start the engine? 26″ (this can vary depending on accuracy of your gauge and accuracy of the weather station giving your your altimeter setting)

Now go land in the same area at a higher elevation, near the same time (so pressure doesnt change much due to atmospheric conditions), say 1,000′ higher. Shut down the engine. Guess what your MAP gauge is going to read? You guessed it, 25″ (assuming it was 26″ when you were 1000′ lower).

This is a FANTASTIC way to know the absolute best case scenario for power available should you need it. You can pull the full 25″ at takeoff (or near it, again – intake tract has some restrictions creating vacuum). You might just exceed limitations, but you have that much power available, but no more. You can also estimate how much you’ll have 2,000′ higher, 5,000′ higher etc etc.

Mark Albom on Jan 16, 2018

Well here goes, so i got into this site or discussion while trying to clear up in my own mind the difference between boost of a turbo or supercharged engine, and normal atmospheric pressure, which does change with altitude. Tha’ts why the contributor with the C-172 may not achieve 75% power when/if he climbs to altitude. We are all taught to become familiar with the owners handbook for each aircraft type we fly, and another falacy is that with a constant speed prop 2400 Prop RPM may not be atainable at all with very low power settings ( MP) .

I was thinking that to understand ( indicated MP) boost in say a turbo engine that I had to add the amount of boost created by the turbo/supercharer to barometric pressure and im still not sure on that score.

It confuses me to hear ( anyone else ???) that an engine is really a suction pump , since a 4 cycle engine which is what were talking about must by design create suction to charge an empty cylinder on the down stroke and then pressure on the compression stroke up to when it fires the spark at the top of the stroke.

I realize that everyone is trying to contribute but starting to question metric or standard Ft/lbs

just gums up the views and information, and so do other non relevant opinions.

I hope to see this article re written to better and more accurately review the Manifold Pressure subject including a photo or drawing of the exact location of the spot where pressure is monitored and sent to the gauge, i believe this would help others as well.

with thanks mark

I plan to re read this article to see if i get it , or get it differently but for now im only a little more confused than when i started, and i have been at aviation for a while.

David M. on Feb 20, 2018

Why can’t manifold pressure adjustments be made automatically instead of manually????

Kodjo on Aug 10, 2018

Very nicely explained. For years I heard pilots in some of my favorite war films speak of losing manifold pressure, and only had a slight notion of what that was. I did suspect intake manifold pressure, and not exhaust manifold. It’s very clear now. I find it interesting that the pressure was measured in mm or in. Hg–like blood pressure!

Muhammad Pervaiz on Feb 12, 2019

Excellent article.

Syed Moniruzzaman on Jun 15, 2019

Dear Sir.

I am Syed Moniruzzaman. AME .

Regards.

SYED AME

randy on Sep 12, 2019

From what i can see, people get confused between vacuum and manifold pressure. First, lets get some terms set.

Vacuum is a relative term. Same as cold. there is no such thing as cold. Its just less heat. So, a perfect vacuum is 0 absolute pressure. If absolute pressure starts at 0, it can only go up from there. That is what your manifold pressure gauge is reading. Pressure above a perfect vacuum. Most have heard of 14.7 psi as standard air pressure. That number is the weight of the air in a 1 inch column from sea level all the way to space. 14.7 psi is also 29.92 hg. So your pressure gauge is reading in hg, not psii, and starting at 0 hg, or 0 psi.

When the engine is idling, the throttle plate is closed, and no load on the engine, vacuum is high, manifold pressure is low. When you open the throttle plate, vacuum goes low, and pressure goes high. Which means since you have less vacuum, you have more pressure.

So, get the term vacuum out of your head, and just think about pressure above 0 absolute pressure, and the manifold pressure gauge starts making sense. The idling engine has the lowest manifold pressure, and the full load engine has the highest manifold pressure.