Effect of Weight on Glide Ratio

Every once in a while I get a question on askacfi.com that I’m pretty sure is a homework question but I still don’t mind answering it. Like the one I just got from Javier who writes asking:

Two airplanes are flying at the same altitude, the same day, same conditios, except airplane A is much heavier than airplane B. Both of them start a power off descent at the same time at the same position. Which airplane will arrive first to the ground? The heavier? The lighter? Both at the same time? Will both airplanes arrive at the same point? This is a question I was asked a few days ago, and I can’t find the correct answer. I would really appreciate if you could help me out.

Holy Smokes that’s a good question! But I think I found your answer from:

http://www.skybrary.aero/index.php/Glide_Performance

Variations in aircraft weight do not affect the glide angle provided that the correct airspeed is flown. Since it is the lift over drag (L/D) ratio that determines the gliding range, weight will not affect it. The glide ratio is based only on the relationship of the aerodynamic forces acting on the aircraft. The only effect weight has is to vary the time the aircraft will glide for. The heavier the aircraft is, the higher the airspeed must be to obtain the same glide ratio. If two aircraft have the same L/D ratio but different weights and start a glide from the same altitude, the heavier aircraft gliding at a higher airspeed will arrive at the same touchdown point in a shorter time. Both aircraft will cover the same distance but the lighter one will take a longer time to do so.

So based on the information above. Here are your answers:

- The heavier airplane will arrive on the ground first

- Yes, the airplanes will arrive at the same point (given the correct speed is flown)

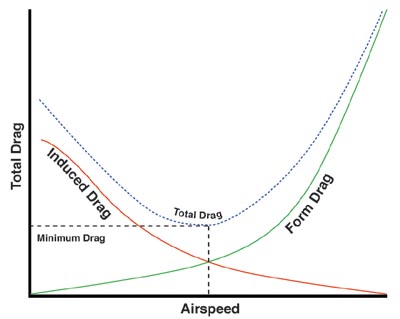

Pilots, do you have your aircraft’s glide speed memorized? This should be a indicated airspeed you should try and maintain the second your engine quits or starts sputtering. This speed is important as it represents the bottom of the drag curve. Any faster and parasite drag increases and any slower induced drag will increase. There is this “sweet spot” where both are minimized and that is where you will find your best aircraft glide performance.

Ever wonder how far you could glide given a certain altitude? Try this Aviation Glide Calculator. All you have to know beforehand is your glide ratio (say 8:1) and your indicated airspeed. (Use your L/D max speed)

Ever wonder how far you could glide given a certain altitude? Try this Aviation Glide Calculator. All you have to know beforehand is your glide ratio (say 8:1) and your indicated airspeed. (Use your L/D max speed)

Paul.

Jim Wolper on Jun 20, 2010

Instead of best glide SPEED, memorize best glide ATTITUDE.

This applies to singles and multis.

This frees you to make the decisions and troubleshoot.

A little extra airspeed has minimal effect, but a little too slow is bad.

JSW (CFII, MEI, CFI-G)

Paul on Jun 21, 2010

Thanks Jim. You’re right, flying the correct attitude is a much better approach to flying the aircraft during emergencies than trying to focus on maintaining a specific indicated airspeed.

Joe on Jun 29, 2010

Come on Paul. You have to explain that a little better than that. This just doesn’t seem to jive. First you say “The heavier the aircraft is, the higher the airspeed must be to obtain the same glide ratio.” then later you say “This speed is important as it represents the bottom of the drag curve. Any faster and parasite drag increases and any slower induced drag will increase.”

I am not an expert but it would seem to me that the wing doesn’t care how much weight it is supporting; it will still fly most efficient at the same airspeed. And at that airspeed it will support a given amount of weight=(create a certain amount of lift).

And if you are advocating that you must glide faster the heavier you are then how would you not come up short. You would have to have a different attitude (sight picture) to achieve this. Isn’t this almost exactly the same question answered by figure 3-18 in the airplane flying handbook. Do you disagree? Why? I am all about learning so help me out here.

Brian on Aug 14, 2010

“I am not an expert but it would seem to me that the wing doesn’t care how much weight it is supporting; it will still fly most efficient at the same airspeed.”

–spacing–

Not airspeed Joe, Angle of Attack. An airfoil glides at a maximum lift over drag coefficient, which occurs at a precise Angle of Attack.

Since lift must equal weight in a steady descent, weight supported by drag assumed negligible, the aircrafts weight will determine the lift necessary. Lift (L) is a product of half of the velocity (V) (speed) squared times wing area (S) times air density (ρ — pronounced rho) times coefficient of lift (Cl):

L = 1/2 V2 * S * ρ * Cl

Since best glide occurs at an exact Cl, we know Cl is a constant. In other words, the Angle of Attack for best glide will not change. We can also assume that wing area (S) is constant and air density (ρ) changes can be neglected. Thus, the only remaining variable left to change our lift is velocity (V), or airspeed.

So what does all this gibberish mean, right? Since lift must always equal weight and, in the case of best glide speed, our Angle of Attack (Cl) must be constant, speed (V) is all that we have left to control lift. Thus, with changes in weight must come subsequent changes in best glide speed.

~Brian

Christopher Ian on Feb 29, 2012

Yes, L/D is L/D always.

Aircraft weight, air density (e.g. altitude) have no effect on the glide ratio.

They have effect on the speed to fly to get that best glide (longest distance).

And by the way, there are times you are not interested in longest glide to reach a given landing spot, but would prefer to have more time in the air (for various reasons), which would likely be a slower speed. Ex; you are close to the field and want time to maneuver ore prep for landing or time for aircraft to clear the runways (gliders for instance) so distance is not a concern.

The first quoted paragraph said;

” Variations in aircraft weight do not affect the glide angle . . . ”

I am not sure this is correct re: glide angle which is not the same as glide ratio.

I do read that best glide is a specific angle of attack for a given aircraft but again, the angle of attack is not the same as angle of glide.

The literature refers to a specific angle of attack, for best glide but how does one know the exact angle of attack, really ? Especially when the angle is so slight.

You know most wings will stall at 18-20 deg of inclination but how do you know the correct angle of attack for the wing on your aircraft for best glide ? ? ?

A C172 w 9.5/1 glide ratio (L/D) has a 6.01 deg. glide path.

Can you or anyone judge 6.01 deg glide path (not angle of attack)

rather than 7.01 or 5.01 ? Really ?

This is important.

A 5 deg angle (glide path) gets you 1909 feet farther while

a 7 deg angle (glide path) gets you 1366 feet less ~

This can be the difference between going home !

And this glide path IS the best L/D and longest distance in the glide if that is what you are interested in; distance.

BUT

glide path is not the same as attitude / angle of attack (AoA).

So tell me (Jim and Paul) what is the AoA for my Citabria or C172 ?

And how do I judge that angle ? ?

So Joe, Jim and Paul are correct but they have not told us how they determine

that specific attitude.

And in fact I would challenge that concept of choosing an ‘attitude’ or angle of attack.

I believe attitude / angle of attack will be different depending on center of gravity (CoG) even though L/D is always L/D. But I am not sure of that.

Brian; ” Not airspeed Joe, Angle of Attack. ”

The airspeed and angle of attack are related directly, yes ?

Just as when you are under power.

I just read elsewhere that altitude / air density does not effect glide ratio but it seems your explanation says it does effect glide ratio.

That is the lesson we learn about slow flight and stalls.

Reduce power but maintain altitude, reduce power some more, maintain altitude.

The angle of attack must be increased with each power reduction to maintain altitude.

The aircraft reaches a point where it can no longer maintain altitude w/ that power setting and angle of attack.

At a critical point – angle of attack, the aircraft can maintain altitude only by increasing power and is said to be behind the power curve.

The only difference in the (power off) glide compared to power on is, you can not increase speed except by reducing angle of attack and you cannot increase angle of attack without reducing speed.

Perhaps I am to understand that angle of attack stays the same in best glide,

while the glide angle can change but glide ratio will stay the same.

Is all that possible ?

Thanks

rizwan on Aug 23, 2012

hi i just wanted to ask that while practicing a flameout landing.. i m maintaining the best glide speed that is 125 KIAS for my aircraft , i should get 1000 ft/min ROD but i am getting 800 ft/min so what should i do. should i maintain the same speed or should i increase my airspeed by increasing dive angle to get 1000 ft .min ROD

Mark on Jan 10, 2013

This is great!! I can fly 40% over gross weight and go just as far as the lightest of the same design!

Mark on Jan 10, 2013

Now that I think of it, I could carry an extra 5,000 lbs. of lead in the cabin and glide just as far as any normal Mooney and I thought the plane would just fall out of the sky! Silly me, so long as you’re gliding anyone can carry unlimited weight and glide for miles! Yippee!

donald cilbup smollo on Jan 26, 2013

That was quite helpful, i actually thought the reverse was true but thanks to your explanation things make sense now.:) keep up the good job

houston on Feb 28, 2014

Mark, not exactly. Remember weight does affect stall speed. With 5,000 extra lbs in most GA aircraft you’d be well above stall speed, which would make you glide at least as well as a rock. All bets are off when the wing stalls.

Airwolf319 on Mar 08, 2014

Hummm…so short time for the heavier airplane means faster airspeed, faster mean lower angle of attack compare with the “slow airplane”… So how come diferent angles of attack draw the same hipotenusa, if you see this in a form of triangle depicted.?

Is posible descent the same distance from the same altitude and land at the same point with diferent angles?… i dont see it.

Pete on Nov 11, 2014

(Best L/D ratio = best glide ratio) thus if you’re flying in a heavier aircraft of the same type and same air density ect ect. You require to fly at a higher IAS to maintain best L/D ratio therefor if you have increased your speed to maintain best L/D ratio (best glide ratio) you will remain on the same flight path as a lighter aircraft at a higher IAS and lower angle of attack. Note as you have increased your IAS (v2) a subsequent decrease in your Angle of attack (cL) is required. L=cL(1/2 x Rho x v2) S

Bart on Jan 10, 2015

Higher weight requires higher lift. Higher lift requires higher airspeed for same AOA. Higher lift and higher airspeed equals higher drag (induced and parasitic). Does the extra weight provide the extra energy to offset the extra drag? Or is the extra drag just neglected in the calculation?

ellielase on Jun 01, 2015

good!

Steven on Jun 14, 2015

Heres one from aerodynamics test:

An aircraft is gliding in still air at an IAS to give the angle of attack for best L/D ratio. If the weight is reduced and the IAS held constant, the glide angle will:

A) decrease

B) increase

C) remain the same

D) be indeterminable

James on Feb 06, 2016

A. At a guess..

Bob on Dec 02, 2017

Assume: XXXX lbs, alt.= 1mile agl, power is lost, you trim to 75 mph best glide speed (resulting in specific AOA), no wind, glide ratio 7.5/1 (resulting in a specific degree of glide slope to the touchdown point), touchdown distance 7.5 miles, glide time 6 minutes.

WHAT HAPPENS IF WE INCREASE THE WEIGHT THE VERY MOMENT THE GLIDE STARTS? NO OTHER CHANGES.

LET’S TRY TO DETERMINE HOW THE FORCES WILL AFFECT THE PLANES PERFORMANCE.

1. With no other changes the plane starts too fall. The added weight requires more lift. The plane must increase speed or AOA to make more lift.)

2. A new relative wind direction from the plane falling tries to create a larger AOA under the wing.

3. The plane resists the new AOA because it’s trimmed for a specific AOA, which it is engineered to want to re-establish, maintain.

4. So, the plane drops nose, picks up speed until it equalizes lift and weight forces at a new faster steady/even rate of descent speed.

4. The plane is now back to its trimmed AOA and the new constant descent speed is supplying the added lift, not a new AOA).

5. Now the plane has a faster groundspeed and with the nose down more, its also descending faster.

WHAT WILL THESE CHANGES DO TO OUR TOUCHDOWN POINT?

TO OUR GLIDE RATIO (AND IT’S RESULTANT GLIDE SLOPE)?

TO OUR GLIDE TIME?

LET’S SEE IF WE CAN CORRECTLY FIGURE OUT THE ANSWER!

HERE’S WHERE MY THINKING MAY GET SCREWED UP. IF I’M WRONG SOMEBODY OUT THERE PLEASE SET ME STRAIGHT.

1. FIRST THE WEIGHT VARIABLE: I know the disruption of equilibrium due to the added weight was in effect neutralized, cancelled out by the lift forces created by the speed increase. The plane is now EXACTLY as buoyant as it was before. Perfect equilibrium. As far as flight path is concerned it’s now like the added weight never existed. The weight is no longer a factor in this scenario.

2. SECOND THE SPEED VARIABLE: I know the AOA did not change. I also know there is a direct relationship between AOA and airspeed. “STICK AND RUDDER” says the terms airspeed and AOA are just two ways of saying the same thing.

So….., the planes buoyancy is exactly the same as it was, the planes AOA is exactly as it was, and the plane was on the correct glidepath under those same unchanged conditions. Why should I think its not on the exact same glidepath now? The only thing that has changed is the rate at which the plane is proceeding along the glide path. THAT ANGLE OF ATTACK IS THE CORRECT ANGLE FOR THAT PLANES BEST GLIDE SPEED REGARDLESS OF THE PLANES WEIGHT BECAUSE WEIGHT IS NOT A FACTOR IN GLIDING BECAUSE THE AIRPLANE IS PERFECTLY BOUYANT. THE ONLY THING WEIGHT DOES IS BRING THE PLANE DOWN THE GLIDE PATH AT A FASTER RATE.

1. THE TOUCHDOWN POINT IS UNCHANGED

2. THE GLIDE RATIO (AND IT’S GLIDE ANGLE) ARE UNCHANGED

3. THE GLIDE TIME IS SHORTENED. YOU GET THERE QUICKER

Well I stuck my neck out on this one. Probably displaying my lack of understanding.

Let me know what you think.

Bob on Dec 02, 2017

To BART, Jan 10, 2015:

Weight opposes lift, it does not oppose drag.

Drag is apposed by thrust.

The extra energy from the weight does nothing to the drag.

It’s the added speed that balances the extra drag,

The extra weight is balanced by the extra lift

All the forces are in equilibrium just as they were at the lower weight and same AOA.

Because the AOA remained unchanged, this once again perfectly balanced plane will remain on its same glidepath and arrive at the same touchdown point.

THE ONLY CHANGE THAT OCCURS IS IT WILL GET THERE QUICKER.

Robert on Dec 02, 2017

To Mark, JAN 10, 2013:

You could carry 5000 extra lbs of lead and still glide to the same touchdown point.

BUT ONLY IF THE PLANE WAS DESIGNED WITH WINGS TO SUPPORT SUCH A LOAD.

That’s why planes have gross weight limits.

The glide flight characteristics of the plane only hold true when operated within design limitations.

Pierre on Apr 05, 2018

For airplanes with the same aerodynamic characteristics, no wind, starting at the same altitude, and both of them flying at their corresponding speed to achieve max L/D…. the heavier plane will reach the ground faster. Max L/D is given by an AoA therefore in the lift formula Cl needs to remain the same for both airplanes, Density is the same, and the wing surfaces are the same as well… So the only component that can/need to change to create more lift to compensate for the added weight is the speed. More speed equals more drag which translate into a higher sink rate…which translate in loosing more altitude for the same amount of time unit… The flight path and the AoA are 2 different things not to be confused. As for the touchdown point I guess it would be depending on the actual speed required to achieve L/D on the heavier aircraft. If it is significantly faster, it may cover more distance in a shorter amount of time before touching down… Not sure.

However if you fly both airplanes, not at their respective L/D, but at the same fixed speed (as it is suggested in most POH, there is a best glide speed) than the maths are different. In GA aircraft, the speed is given in reference to the max weight. Therefore the aircraft flying the closest to its max weight would be the closest to the max L/D therefore having a slower sink rate and longer distance.

Ben Trapnell on Apr 12, 2018

Wow! A lot of misinformation going on here. Gliding Distance is given by

altitude (h)xL/D.

Notice, there is no weight given here. Also, there is no thrust to move the aircraft. What gives? There is a forward component of weight (relative to Drag) that moves the aircraft forward. It is found by multiplying the weight by the sine of the glide angle. (if I could put a figure in here I would draw out the vector relationship). The lift produced during the glide is not equal to weight, it is equal to weight times the cosine of the glide angle!

L=Wcos(glide angle)

D=Wsin(glide angle)

L/D=1/tan(glide angle)

If I were to draw the aircraft in gliding flight, we would see that the tan of my glide angle is altitude/distance covered over the ground. tan(glide angle)=alt/distance.

Solve for distance we get: distance=tan(glide angle)/altitude

If you remembered that L/D=1/tan(glide angle), we could substitute L/D in the above equation (because the tan(glide angle) cancels the 1/tan(glide angle) and we get (drum roll please)

distance (gliding)=L/D x altitude

The F-4 Phantom had a respectable L/D of about 8.7. If the C-172 has an L/D of 9.5. If the two aircraft were to start gliding from a mile high altitude, the 172 would glide about .8 miles further than the phantom. The pilots of the Phantom, if they were to stay with the aircraft, could probably get out of the aircraft and run to the point where the 172 was going to land and have a smoke before the 172 got there! (just kidding…)

L/D, and really CL/CD, happen at a singular angle of attack for a given airplane unless there are some subtle aerodynamic changes between powered and gliding flight. For a 172, there is a significant difference between powered L/D vs gliding L/D due to the additional drag of a non-powered rotating propeller.